A word or two of warning before you begin. This is somewhat different than what I usually write. It certainly lives in the same world as the other posts on this blog, but there is more to it than usual. It is also very long. You might want to grab some trail mix and a bottle of water before embarking.

A little more explanation and background is needed as well. I’ve done some teaching of comics, and I’ve read a lot of comics history and comics academia in the last few years. I have aspirations of writing this sort of thing (as you might know if you’ve read any of the other entries on this blog). My caveat here is that I know that I will never be a hard core academic… not at this stage. I find a lot of pure academic writing to be, frankly, boring. A lot of it seems to me to be academics arguing academic theory with each other and never saying anything that relates to anything else. Yes, I know, that’s the point of a lot of academic writing. It’s not meant for the layperson.

But comics and other pop culture topics come from the world of laypeople. It has always seemed odd to me to talk about them in ways that alienate the people who enjoy them. I think there has to be a happy medium.

Anyway, late last spring I saw a call for academic papers on the topic of the intersection of comic books and David Bowie. This seems like it would be a very narrow topic, but as a friend of mine said when he saw the CFP, “You know, I know a guy.” That guy would be me. Anyone who knows me knows that along with comics music is my other big hobby. I’m a massive fan of Bowie and have read, for fun, two collections of academic essays on him and his work.

So I spent last summer doing research and crafting a paper that I eventually submitted. It was rejected. I can’t say I was surprised. I recognize that there are many aspects of academia that I am just not skilled in. I knew that going into it. Though, if I was going to be rejected, the following response is the best kind of rejection to get.

“While we appreciated the creativity, vision, poetics, and originality of this piece, the overall lack of academic rigour made it unsuitable for publication…”

Given what I want to do with my writing and the audience I want I guess I’ll take “creativity, vision, poetics, and originality,” over “academic rigour.”

Many thanks to my beta readers, Marcel and Leigh Anne, for their insight and suggestions. Lots and lots of thanks for the guidance, encouragement, and forbearance of my academic guru, Dr. Michael Chemers (and thanks for making my conversation with Mike Carey possible).

So, after much ado, without further ado, here’s my paper, with endnotes and references and everything.

‛See my life in a comic/Like the way they did the Bible’: Viewing Bowie’s Starman as an avatar of the rise and fall of human consciousness.

Abstract

David Bowie, through his music and his image, has always been a liminal figure, most noticeably in breaking down the gender binary through androgyny and sexuality. In comic books his likeness has been used by writers and artists in their depiction of Lucifer. But before Bowie influenced the comics that came after him, he himself tapped into many of the same ideas and images as the comics creators that came before him.

This paper will trace the repetition of these themes and braid together the various influences from comic books, science fiction, philosophy, and the occult that informed the creation of David Bowie’s music and performance. We will see how Bowie’s personas connect these disparate ideas and how they embody the concept of the manifestation of divine consciousness in the material world. We will explore the idea that Bowie served as an avatar of both rebellion and inspiration to his fans and that there is a kind of freedom in rebellion against those who try to control us. We will explore the idea that his work was as much about spirituality as it was music and fashion.

Introduction

“I was drawing on Blake in a lot of this, with Yahweh as the power that limits and defines, and Lucifer as the power that pushes against limits and transgresses.”

– (M. Carey, personal communication, July 13, 2016).

In the beginning, it is said, there was Heaven and the Earth, the sacred and the profane, the wicked and the divine. In the liminal space where these things meet lies the Venn diagram of the human struggle with spirituality. When we eat from the Tree of Knowledge are we turning away from the divine, or are we taking the first step in becoming divine ourselves? Did we fall from the Garden or were we pushed so that we could find our wings?

To discuss the connection between David Bowie and comics there must be a distinction between Bowie the man and Bowie the icon. He was a liminal figure in many regards, a psychopomp for the psychedelic generation, traveling freely between the spheres in mercurial fashion. The specifics of his biography often take second place to the iconography he created through his music and performance.

Early designs of the character Dream in the pages of the DC Vertigo Comics series Sandman look like Bowie, but over time Dream came more to resemble series writer Neil Gaiman. (Geenie, 2016). Gaiman introduced the character of Lucifer, the lord of Hell early in the series. Drawn by Mike Dringenberg, from this first appearance onward Lucifer looked like David Bowie.1 Kelley Jones, artist of a later story arc featuring Lucifer has said Gaiman instructed him, ‛You must draw David Bowie. Find David Bowie, or I’ll send you David Bowie. Because if it isn’t David Bowie, you’re going to have to re-do it until it is David Bowie.’ (McCabe, 2004).

Why was Bowie an appropriate choice to base the character of Lucifer on? A cursory search of the internet yields thousands of results detailing Bowie’s interest in the occult, ranging from well-researched to paranoid conspiracy theories. A survey of his lyrics and imagery, and the ideas that preceded them in comics and the occult may bring light to the topic.

In Bowie’s song Station to Station we hear the lyrics: ‛Here are we/One magical movement/from Kether to Malkuth/There are you/You drive like a demon/from station to station.’ (Bowie, 1999). Kether to Malkuth is a reference to the esoteric Judaic system of the Kaballah, a set of teachings meant to explain the relationship between the eternal world of the divine and the mortal universe of man. On the album we see Bowie drawing the Tree of Life diagram of the Kaballah. Kether is the topmost sephirot, the crown of the Tree. It refers to that which is above all comprehension. It is the divine essence of creation, never to be understood because it sits above all mental knowledge. At the bottom is Malkuth, the tenth sephirot. It represents the ways in which God manifests through his creation and the way mortals can apprehend the divine in the material world. Moving from Kether to Malkuth indicates the pathways by which the divine can appear in the mundane. (Berg & Berg, 2002).

The phrase ‛Station to Station’ can also reference the Catholic Stations of the Cross, a series of prayers based on the pathway Jesus took to Golgotha on the day of his crucifixion. The first Station is when Jesus is condemned to death. The final is his resurrection from the dead. This sequence can be seen as symbolically opposite of the Kaballah in that rather than showing the divine descending into the corporeal world it illustrates the pathway of the profane being resurrected and becoming divine. These twin images of ascending and descending, the rise and fall, indicates the communication between the realms of Heaven and Earth goes both ways.

The Superman Who Fell To Earth

The creation of Bowie’s performative personas, specifically Ziggy Stardust, was influenced by precedents to be found in comic books, science fiction, philosophy, and the occult, as well as many other sources (Goddard, 2015). These ideas and images thread through his entire career. A comprehension of how these influences combined in his characters is essential to understanding how Bowie became associated with comic book versions of Lucifer.

In 1976 Bowie starred in The Man Who Fell to Earth, a film directed by Nicholas Roeg based on a 1963 novel by Walter Tevis. The title alone creates a resonance with Lucifer, the fallen angel. The movie follows the story of Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien who comes to earth looking for salvation for his dying world. Just four years earlier Bowie had debuted his concept of an alien rock star named Ziggy Stardust.

Unlike Newton, Ziggy was not looking for salvation. He was bringing it. The song cycle on the album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, while not providing a specific or cohesive narrative, alludes to the story of an alien messiah come to earth to ‛blow our minds,’ a phrase that can be interpreted to mean enlightenment or cosmic consciousness. Like any messiah, Ziggy pays the ultimate price by engaging in a willing sacrifice as a rock and roll suicide. He leaves this world with a final positive message of, ‛You’re not alone… and you’re wonderful.’ (Bowie, 2002). Similarly, in the Gospel of Luke Chapter 23, Verse 43 while on the cross Jesus says, ‛Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.’ You’re not alone.

In addition to the Christ metaphor inherent in any messiah story, there are precedents in the world of science fiction and comic books. The 1961 Robert Heinlein novel Stranger in a Strange Land tells the similar story of Michael Valentine Smith, a human raised by aliens on Mars. As an adult he comes to earth and founds the Church of All Worlds to teach his remarkable powers to humanity. Those who do not learn will eventually die out, leaving behind a new race of humans, the homo superior. Smith is eventually killed by the mob of humanity who are not ready for his mind-expanding lessons.

The similarities in this tale of an alien messiah to that of Ziggy Stardust cannot be overlooked. Bowie used the same terminology in his lyrics. In the song ‛Oh You Pretty Things’ from Hunky Dory he sings, ‟Gotta make way for the homo superior.” (Bowie, 1990). The term homo superior first appeared in comics in X-Men #1 in 1963 as a description for mutants, those people in the Marvel Universe born with super powers due to genetics altered by radiation.2 This term has been linked to the idea of the Ubermensch, primarily as it is used in the book Thus Spake Zarathustra by Friederich Nietzsche.

The Ubermensch concept played directly into the creation of another alien savior who fell from the sky. Superman first appeared in Action Comics #1 in 1938, wearing primary colors and creating the tropes of the superhero genre and archetypal imagery associated with it. Superman’s origin is perhaps the most well-known story in comics. He is an alien who fell to Earth when his home planet Krypton was destroyed. He developed amazing powers far beyond those of mortal men and vowed to use them to help the people of Earth.

There are aspects of Judaism encoded into Superman that are well documented, as might be expected since his creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, were Jewish. The name Kal-El, Superman’s Kryptonian name, translates from the Hebrew as ‛All that is God.’ Elements of the story of Moses, as well as the concept of a Messiah who would one day arrive and save us all can be read into the Superman narrative. (Brod, 2012).

Superman is also, symbolically speaking, a sun god. He stores the energy of the sun in the cells of his body and converts it into strength, invulnerability and all of his other powers. Like Ra and Apollo, mythic sun gods who preceded him, he is the light bringer who banishes the darkness.

So it’s no wonder that in spite of his Jewish origins Superman is regularly cast in the light of Christian iconography. Through imagery and story we have seen Superman as a metaphorical Jesus. In 1993 he died, sacrificing himself to save the Earth. (Jurgens, et al., 2013). He was resurrected a year later, completing the cycle. While resurrected gods play a part in many religions and mythologies, in the western world this is usually interpreted as the story of Christ.

Bowie was certainly aware of superheroes and the potential of their symbolism. In 1970 he formed a new band called The Hype. Each member assumed a superhero identity and costume for their stage show. Bowie was Rainbow Man. This laid the groundwork for much of what would come later. (Trynka, 2011).

Siegel and Shuster were not the only people in the 1930s using the idea of the Ubermensch. Adolph Hitler and the Nazi party adopted the concept as philosophical justification for their ideas of a Master Race. Seen through this lens the idea of a Superman is something for the average person to fear. If a race of supermen appeared on earth what would stop them from subjugating everyone else? Absolute fascism is the most likely result.

This idea was attributed directly to Superman in the book Seduction of the Innocent by Dr. Frederic Wertham in 1954. This influential and deeply flawed academic study claimed that comic books were the cause of all juvenile delinquency. Wertham believed that the very concept of the superhero was a fascist idea, writing, ‛Superman (with the big S on his uniform—we should, I suppose, be thankful that it is not an S.S.) needs an endless stream of ever new submen, criminals and ‛foreign-looking’ people not only to justify his existence but even to make it possible.’ (Wertham, 1972).

Bowie was also linked to Nazi sentiments during the Thin White Duke era and the period of Station to Station. There is an infamous picture of him at Victoria Station giving what looked like a Nazi salute. In a 1976 Rolling Stone interview he was quoted as saying, ‛I think I might have been a bloody good Hitler. I’d be an excellent dictator. Very eccentric and quite mad.’ (Crowe, 1976). Was this something he actually believed, or was it meant to be provocative, part of the character he was portraying at the time? This was during his coke-fueled years where he admits to paranoid ideation. ‛It was probably one of the worst periods of my life,’ he said thirty years later. ‛I was undergoing serious mental problems… It’s a blur, topped off with chronic anxiety, bordering on paranoia.’ (Crowe, 2006).

Bowie’s lyrics on songs such as ‛Oh You Pretty Things’, ‛Quicksand’, and obviously ‛The Supermen’, show that he was giving thought to Nietzsche’s idea of the Ubermensch. The mix of comic book imagery, philosophy, and the occult were converging for him.

Obviously, the dark side of the Ubermensch can be a dangerous idea. The overriding subtext of the X-Men has been the battle between homo sapiens and homo superior. The X-Men are vowed to ‛protect those who fear and hate them,’ as their tagline goes. (Kirby & Lee, 2011). This fear is also the basis for Lex Luthor’s enmity for Superman in most modern interpretations of their relationship. This idea asks the question, ‛What is the place of human beings in a world where Supermen exist?’ Anyone who transcends or steps outside of the status quo threatens the accepted parameters of societal strictures.

In the recent Zach Snyder movies, Man of Steel, and Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, we see a darker vision of this savior from above, one where humans are more afraid of him than in awe. Symbolically speaking, Batman can be read as the god of the underworld in opposition to Superman’s god of the sky. However, in the second film, he embodies the human reaction to the alien. Even though Batman, more than anyone, has proven that he can become an Ubermensch, he still fears the alien who represents heights he cannot achieve. He attempts to murder Superman, creating a kryptonite spear (reminiscent of the spear that pierces Christ’s side on the cross). Superman dies, but there are hints of his resurrection in future films.

In spite of the movie’s assertion that Superman’s S symbol stands for Hope, what we see is a world that is very afraid of this god-like being from the stars. Superman is viewed not as a being of light who inspires humanity, but instead as an alien who leaves death and devastation in his wake, something to be destroyed. It seems there is always a large contingent of society who choose fear over hope. Rather than being inspired by superior achievements or behaviors that challenge the norm the response is more typically fear and resentment. This is an inherent part of the Christ story. His teachings have inspired his believers for centuries, but at the time were an act of rebellion against the Roman Empire and the religious dogma that had preceded him. Rebellion in the name of personal growth is anathema to the groupthink of the masses.

Jesus Christ brought what was at the time a radical new approach to spirituality and was crucified for his efforts. Ziggy Stardust blew our minds, but in the end the kids had to kill the man. The Superman who fell to Earth is not seen as our savior. He is instead seen as the means of our destruction.

Which brings us back to another powerful being who fell to earth: Lucifer.

The Rise and Fall

The name Lucifer appears only once in the Bible, in Isaiah 14:12; ‛How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning!’ Contextually, this quote refers not to Satan or any other demon from Hell or fallen angel, but to Nebuchadnezzar II, King of Babylon. Translated from the word hêlêl (transliterated from the original Hebrew), it loosely means ‛Shining One’ or ‛Light Bearer.’ (“Hebrew Concordance: Hê·lêl — 1 occurrence,” 1966). It wasn’t until works like Paradise Lost by John Milton and Dante’s Inferno that the name became popularly associated with Satan. (Kohler, 2003). Like Bowie, the devil has worn many guises, and it is beyond the scope of this essay to catalog all of them. It is the Luciferian tradition, inspired by Gnosticism, that addresses the issues presented here.

The Book Of Lucifer from The Satanic Bible espouses the idea that Lucifer, rather than being evil, is an agent of enlightenment. This idea is expounded upon in the Dictionary of Demons. ‛Lucifer remains still a creature of light, but has chosen to descend into the Human realm in order to bring his light into Humanity.’ (Gettings, 1988). In this view the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge is self-awareness, without which human beings could not grow. Lucifer is the agent who gives humanity the opportunity to grow spiritually. Minus the references to Lucifer, this is what the Kaballah’s journey from Kether to Malkuth symbolizes as well. Given his lyrical references it is likely Bowie was exposed to these ideas through the writings of Aleister Crowley and some of his followers. (Trynka, 2011).

Bowie served as a metaphorical snake in the garden of British society. While there are many aspects of his career that have challenged the status quo it was his appearance as an androgynous alien in 1972 that was his first far-reaching act of cultural rebellion. Homosexuality was forbidden fruit. His provocative claim that, ‛I’m gay. I always have been,’ in an issue of Melody Maker said to a generation of young people that they did not have to be constrained by the definitions of their elders (Watts, 1972). His performance of the song ‛Starman’ on Top of the Pops on July 6, 1972 lit a fire of controversy and public backlash. It also served as a rally point for his youthful fans. ‛But when he draped an arm over Mick Ronson’s shoulders for part of ‛Starman,’ Bowie established himself as a rebel… the televised moment was eye-opening. With an arm and a costume, Bowie had helped some people begin to rethink what they knew about gender and sexuality.’ (Hepworth, 2016). The lyrics he sang that night, ‛Don’t tell your poppa or he’ll get us locked up in fright,’ (Bowie, 2002), seem to show an awareness that he knew what he was bringing to the world at that time.

This reflects not only the idea of Lucifer as Light Bringer, but also the mythic story of Prometheus, and many other Trickster gods, of stealing fire from the heavens to give to humanity. Fire is what set humans apart from animals, in terms of its actual use and as a symbol of intelligence and enlightenment. Fire came to early man from the sky in the form of lightning. This godlike power descending to earth from the heavens is why so many ancient gods are depicted wielding a lightning bolt as a weapon. (Werblôwsqî, 1973).

The symbol of lightning has a long tradition as one of the most repeated icons in superhero history (Morrison, 2011). The Golden Age Captain Marvel first appeared in Whiz Comics #2 in 1940. Young Billy Batson travels through an underground cavern and meets a wizard who gives him a magic word. When he says SHAZAM he is struck by lightning and imbued with the godlike power of six mythical beings.3

In the pages of Miracleman,4 a deconstruction of Captain Marvel, writer Alan Moore directly tackled the concept of the Ubermensch, by using a quote from Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra. ‛Behold, I teach you the Superman. He is this lightning. He is this madness.’ (Moore, et al, 1988). The cover of Bowie’s 1973 album Aladdin Sane, with its iconic lightning bolt slash across his face and the punning reference to insanity, seems to embody this quote as well.

We can now see how Bowie borrowed the ideas of Nietzsche’s Ubermensch, tropes of the comic book superhero and science fiction, and aspects of occult philosophy and used them to create Ziggy Stardust, a character who was an amalgamation of these and other influences. Ziggy’s success in the early 1970s challenged established views of sexuality, fashion, music, and modes of behavior. It is this aspect of Bowie, the rebel who enlightens and inspires, that is the basis for comics creators using his image in their portrayal of Lucifer. Two specific examples of this can be addressed.

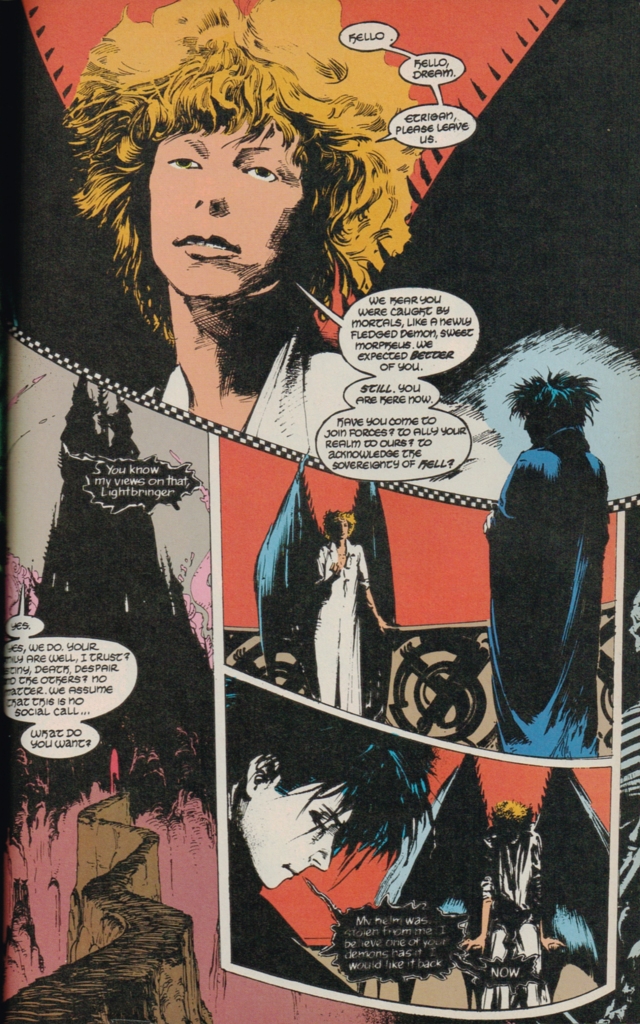

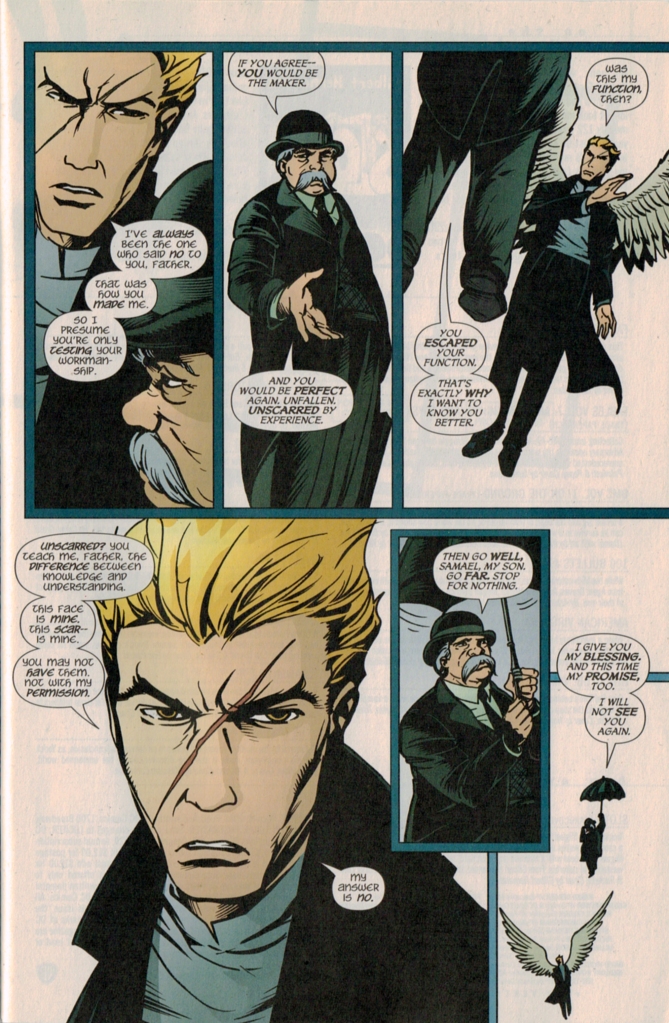

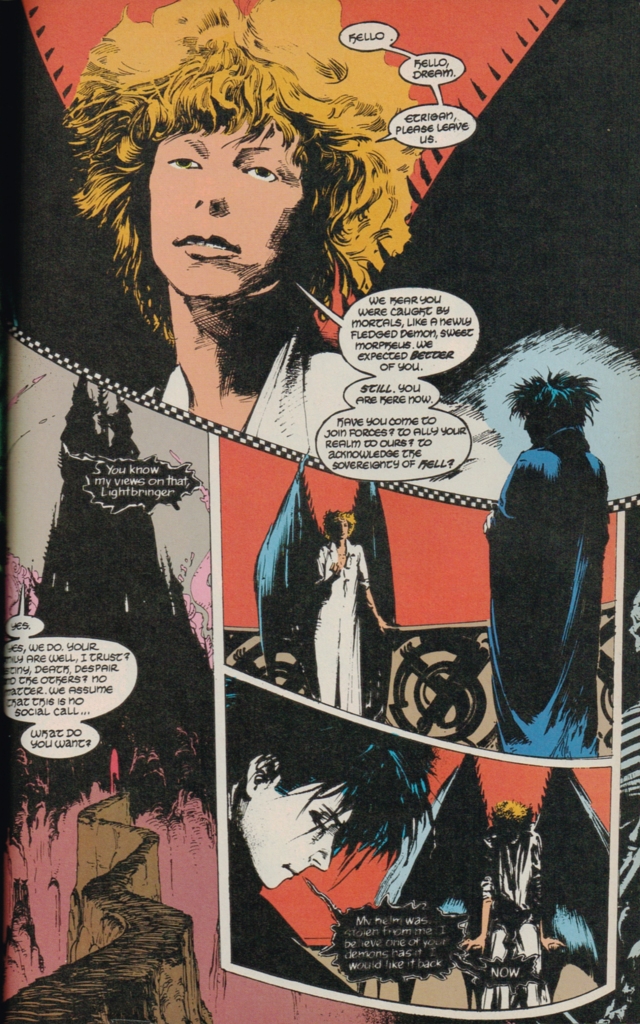

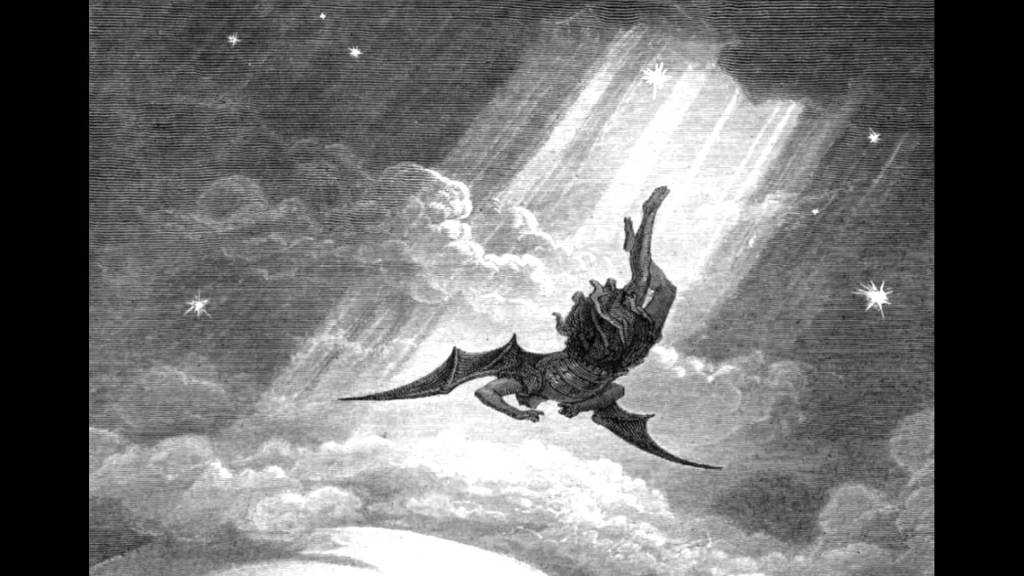

When Lucifer first appears in Sandman, Morpheus of the Endless, the Lord of Dreams, has journeyed to Hell. ‛Greetings to you, Lucifer Morningstar,’ Dream says. We see Lucifer’s face, bearing an uncanny resemblance to David Bowie on the cover of the album Space Oddity. He is dressed in a white suit and sporting giant bat wings, an allusion to both the Thin White Duke and any number of Gustave Dore illustrations for Paradise Lost. (Gaiman, et al, 2003).

Figure 1. Gaiman, N. [w], Dringenberg, M. [a], (2003). The Sandman, Volume 1: Preludes and Nocturnes (17th ed.). New York: DC Comics. © DC Comics.

Figure 2. Cover of the Space Oddity album by David Bowie

Figure 3. Gustave Dore illustration with bat wings

The bat wings serve to differentiate Lucifer’s status from other angels, those who have not fallen, who sport the traditional pure white feathers. In a later storyline, The Season of Mists, Lucifer asks Morpheus to cut his wings off. He is giving up his rule of Hell. It is established that Lucifer has never tried to lure souls there. ‛I don’t make them come here… And how can anyone own a soul? No, they belong to themselves… they just hate to have to face up to it.’ (Gaiman, et al., 1992). Lucifer is tired of his role. Humans choose Hell over enlightenment and he is tired of reigning over their failure. Cutting off his wings is a rejection of his role as the Adversary and begins his quest to regain his status as a bringer of light.

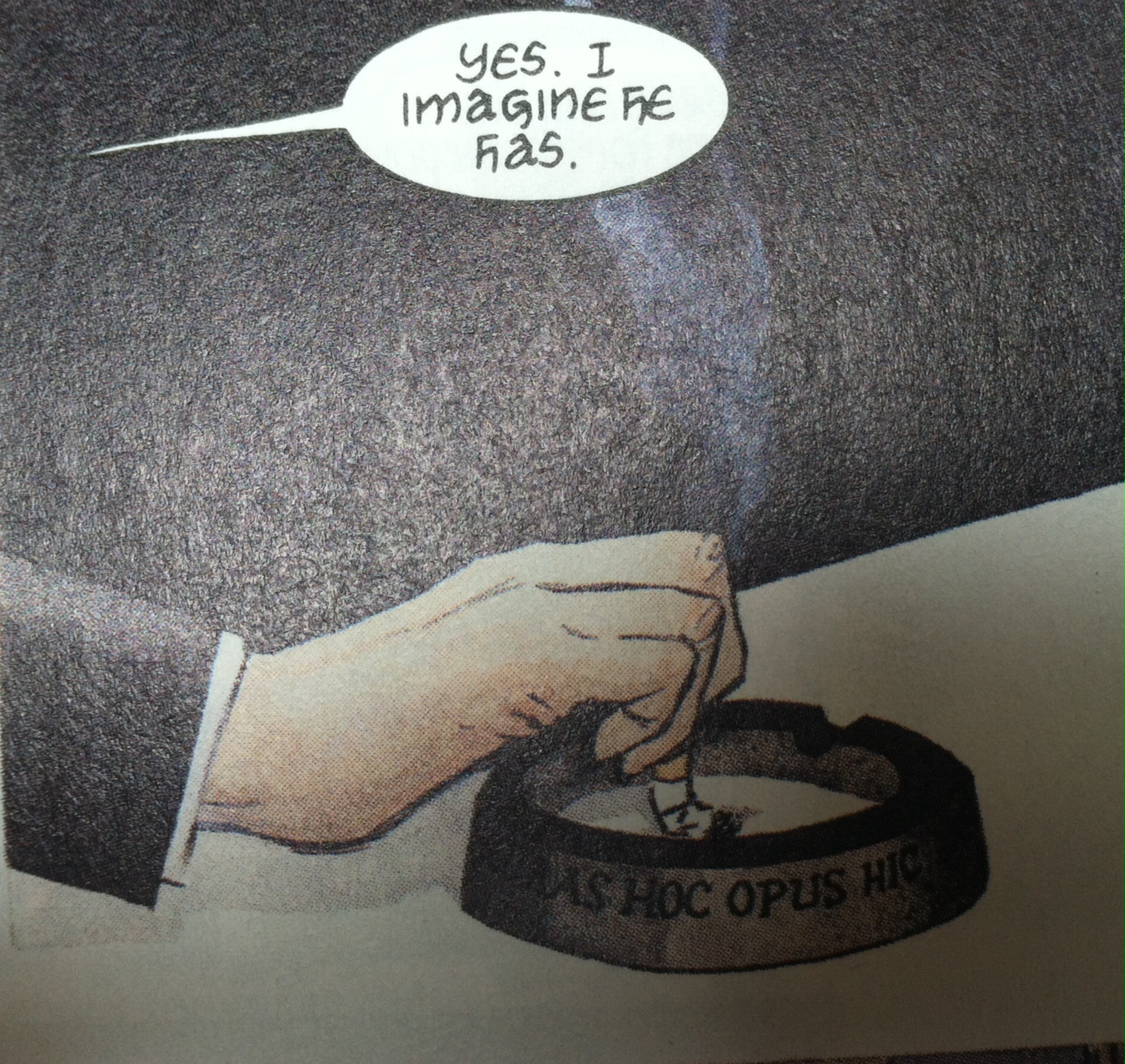

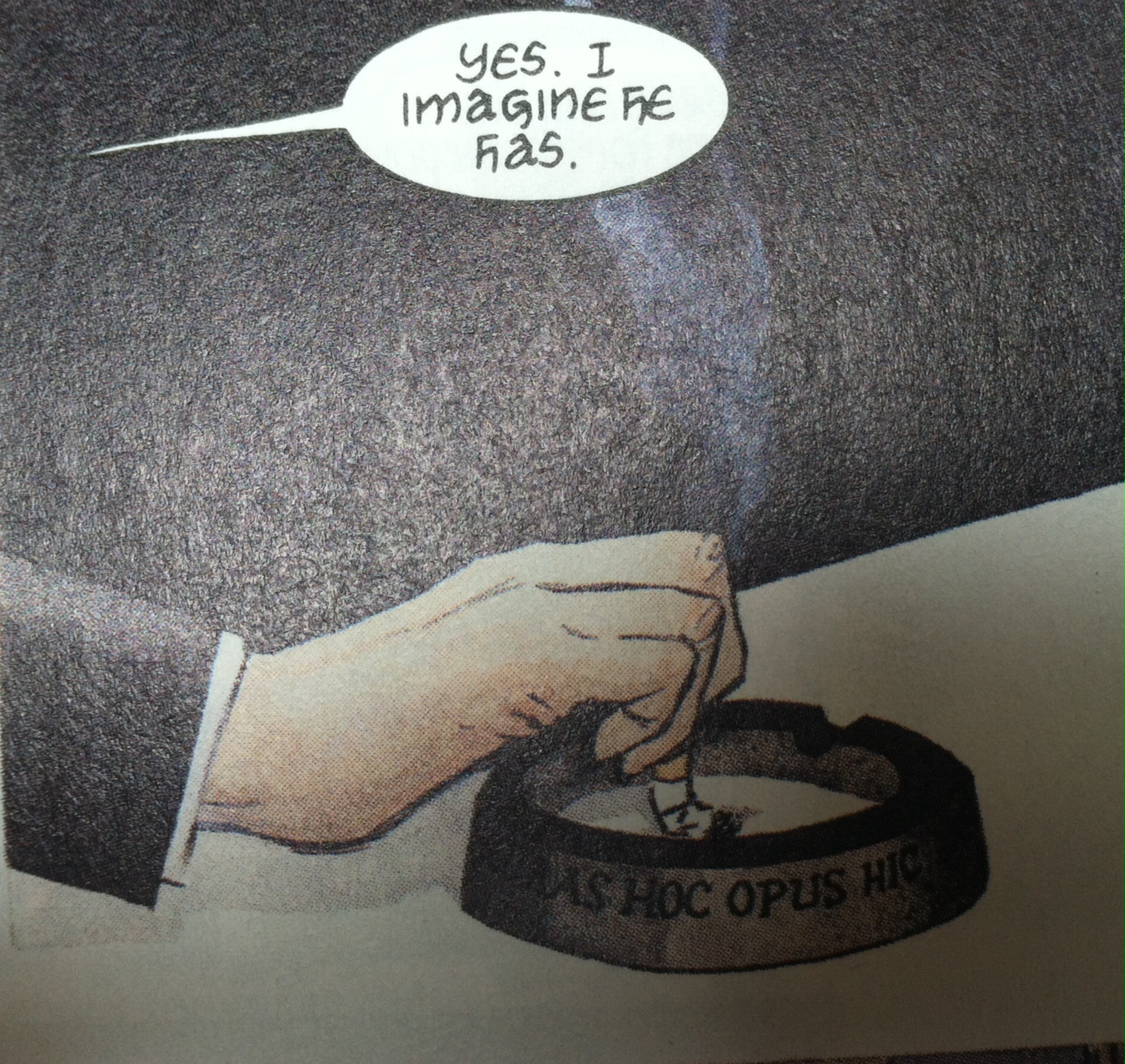

In the first issue of the ongoing Lucifer series from DC/Vertigo we see the now ex-lord of Hell sitting in his Club, the Lux, smoking a cigarette. Inscribed on his ashtray is the Latin phrase, Hoc opus, hic labor est. (Carey, et al., 2013).

Figure 4. Carey, M. [w], Gross, P. [a], (2013). Lucifer: Book One. Burbank. New York: DC Comics. © DC Comics.

This is part of a quote from the Aeneid, by Virgil, which sums up the difficulty of returning to a state of the divine once one has fallen. ‛The gates of hell are open night and day/Smooth the descent/and easy is the way/But to return, and view the cheerful skies/In this the task and mighty labor lies.’ (V., & Fagles, R. 2006). The task and mighty labor is in striving toward the light while still being embodied in the physical plane. Or, as the Bowie song says, ‛It ain’t easy to get to heaven when you’re going down.’ (Bowie, 2002). Enlightenment is not a sudden transcendence but an ongoing process of burning away the dross and looking within for that which resonates with a higher self-awareness.

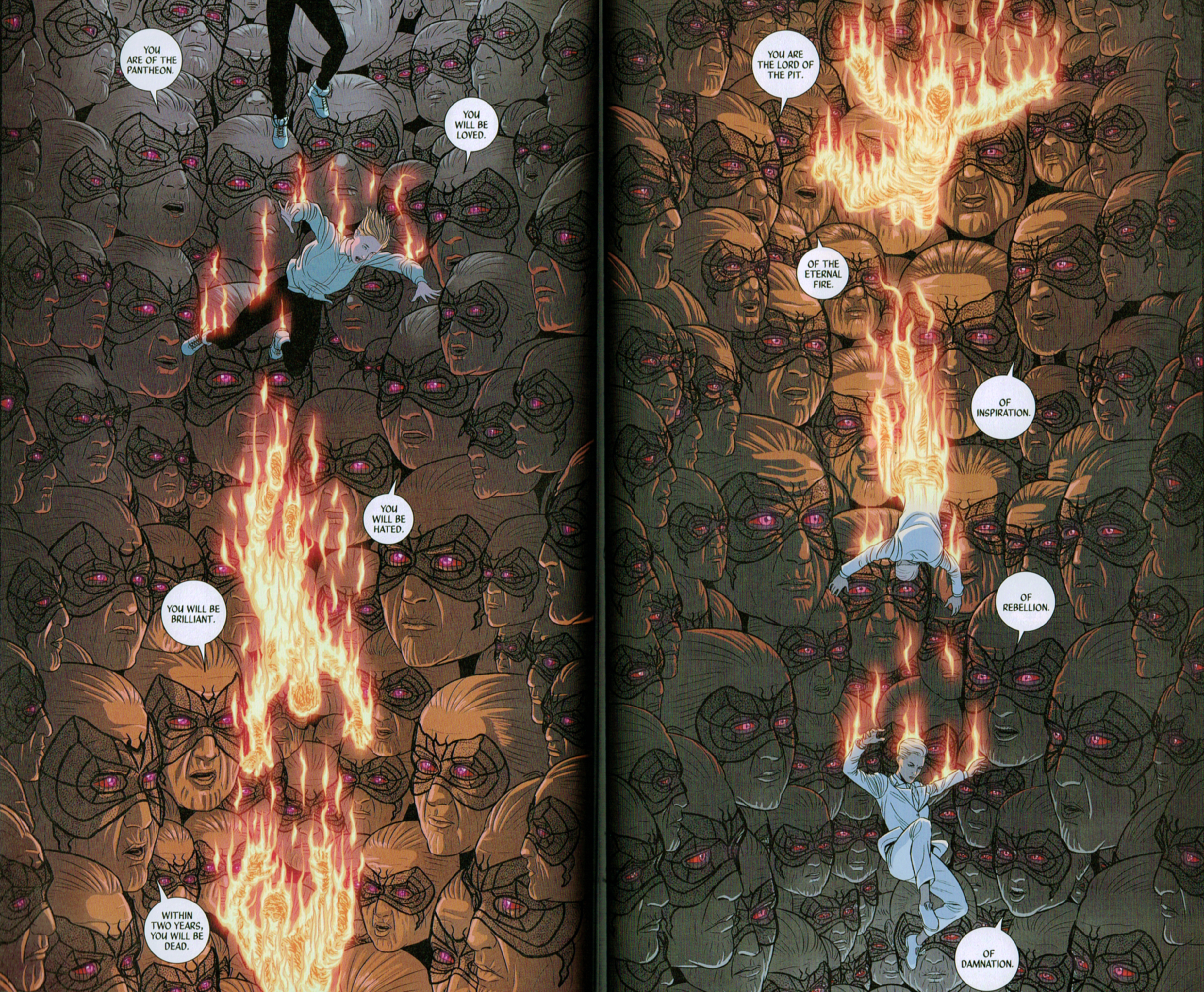

A second iteration of a Bowie-inspired Lucifer has appeared more recently in the pages of the Image comic The Wicked and the Divine by Kieron Gillan and Jamie McKelvie. The core description of the series is, ‛Every ninety years twelve gods return as young people.’ (Gillan & McKelvie, 2014). They are fated to be loved and hated, and in two years they will all be dead. In 2014 they reincarnate as beautiful pop/rock stars. Comparisons can be drawn between many of the characters and real life rock stars. In the first issue we are introduced to Luci, the avatar of Lucifer. Her appearance is overtly based on David Bowie as the Thin White Duke (with more than a little bit of Tilda Swinton in the mix as well).

Figure 5, 6, 7. Gillen, K. [w], McKelvie, J. [a], Wilson, M. [a], (2014). The Wicked and the Divine: The Faust Act: Volume 1. United States: Image Comics. © Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie. This image, used as a variant cover, was based on the mugshot of David Bowie taken at the the time of his arrest in Rochester, NY on March 25, 1976.

Each is born as a normal human being, but at some point in their life a god descends into their consciousness. They retain the memories of their human lives, but are also aware of the lives of the gods they now embody. In the course of the series the characters obliterate traditional binaries of gender, race and culture, and sexuality, echoing tropes of rock and roll performance that have part of their genesis in Ziggy Stardust. Lucifer appears here as a woman, while Inanna, the Queen of Heaven, appears as a bisexual man. Urdr, Norse goddess of prophecy, is a transgender Asian woman. The power of the gods, once they have descended into the corporeal, transcends any human distinctions.

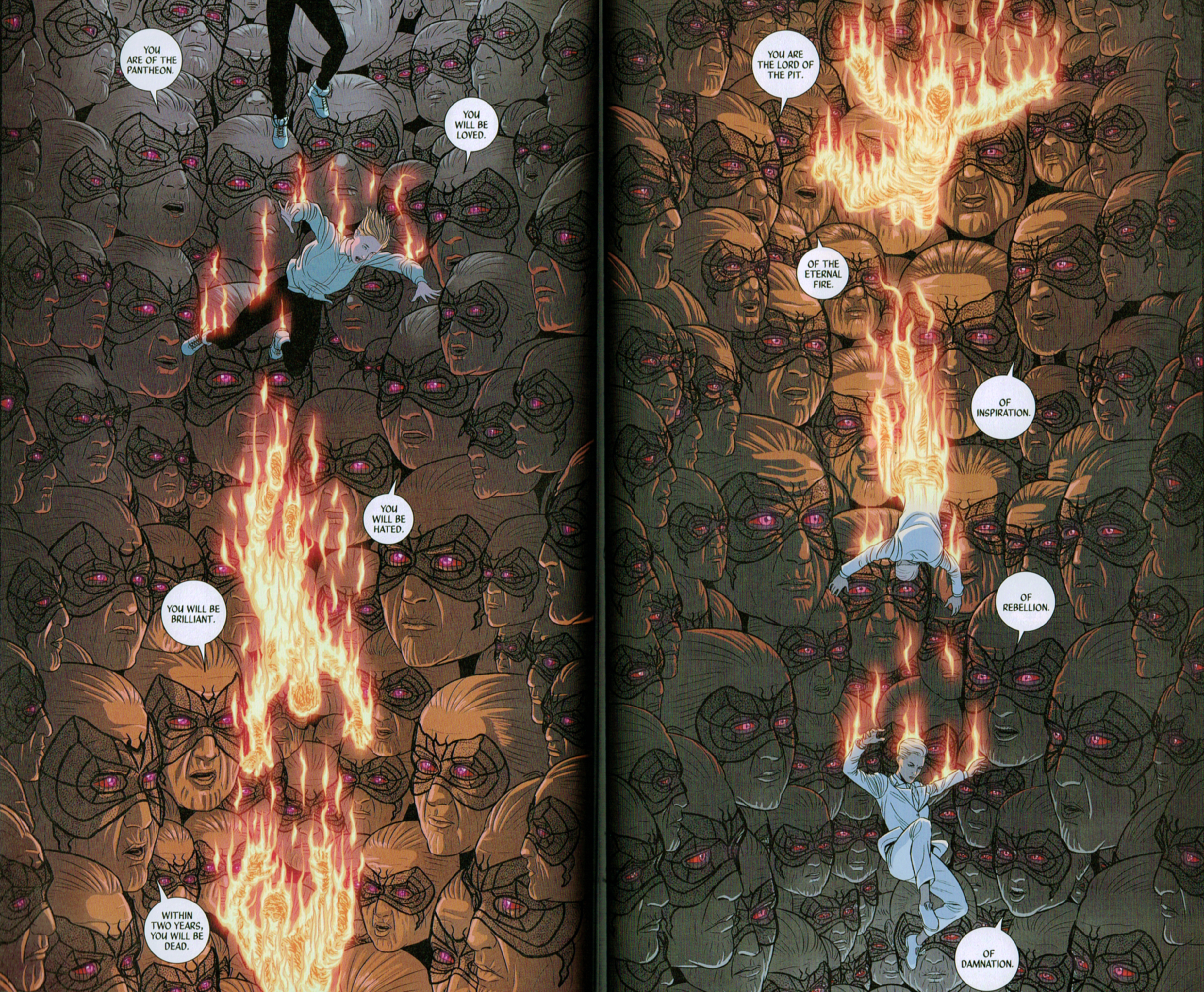

The image of this descent plays an important role in the series, reflecting classic images of Lucifer’s fall from Heaven. When teenager Eleanor Rigby (her parents were Beatles fans), encounters an ancient woman named Ananke her life is forever changed.

Figure 8. Gillen, K. [w], McKelvie, J. [a], Wilson, M. [a], (2014). The Wicked and the Divine: The Faust Act: Volume 1. United States: Image Comics. © Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie.

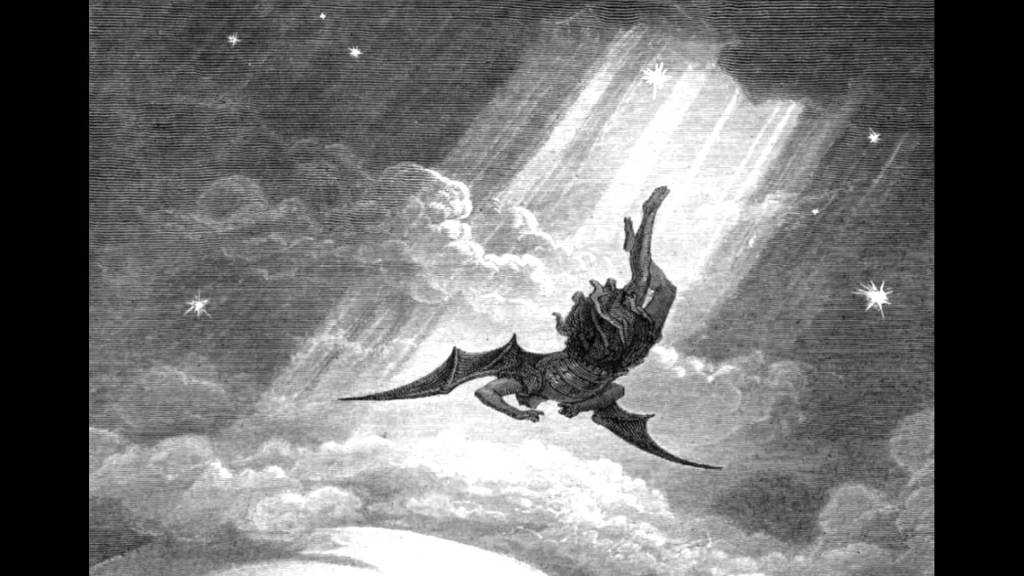

Figure 9. Gustave Dore illustration of Lucifer’s fall.

As seen in the two page illustration above, she falls, her essential humanity being burned away from her as she is inhabited by the essence of Lucifer. ‛You are the lord of the pit,’ Ananke says. ‛Of the eternal fire. Of inspiration. Of rebellion. Of damnation.’ (Gillan & McKelvie, 2014). When the process is over we see Eleanor, now transformed into Luci, kneeling on the scorched ground, surrounded by white feathers, symbolic of her nature as a fallen angel.5

Figure 10. Gillen, K. [w], McKelvie, J. [a], Wilson, M. [a], (2014). The Wicked and the Divine: The Faust Act: Volume 1. United States: Image Comics. © Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie.

The specific mention of inspiration and rebellion is important, and as we have seen, implicitly references Bowie’s performance of Ziggy Stardust. Inspiration ties in with the Luciferian idea of enlightenment. One can reach for the heavens only if they are inspired to be more than they already are. Any act that raises human consciousness above that of the status quo is an act of rebellion.

In The Wicked and the Divine it becomes apparent that Ananke is not the caring overseer of the gods she at first appears to be. She has a purpose beyond that of the reincarnated gods, and they are expendable if need be to further her goals. Luci is the first victim of Ananke’s plan, though not before she inspired others to rebel.

The name Ananke comes from the ancient Greek goddess of fate and necessity. (‛Ananke’, 1999). The question this raises is the age old conflict between fate and free will. Lucifer, by tempting Adam and Eve to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, made them aware of choice, which is absent in the presence of fate. Enlightenment, illumination, self-awareness, however the search for the divine is defined, is awareness of this choice. What the fallen angel offers is the choice of personal responsibility and self-determination instead of blind adherence to rules and the dictates of fate.

The problem with the question of free will is that it may never be possible to determine if it actually exists in a universe with an all-knowing god. ‛You know…,’ Lucifer says to Dream, ‛I still wonder how much of it He planned. How much of it He knew in advance. I thought I was rebelling. I thought I was defying his rule. No… I was merely fulfilling another tiny segment of His great and powerful plan.’ (Gaiman, et al., 2011).

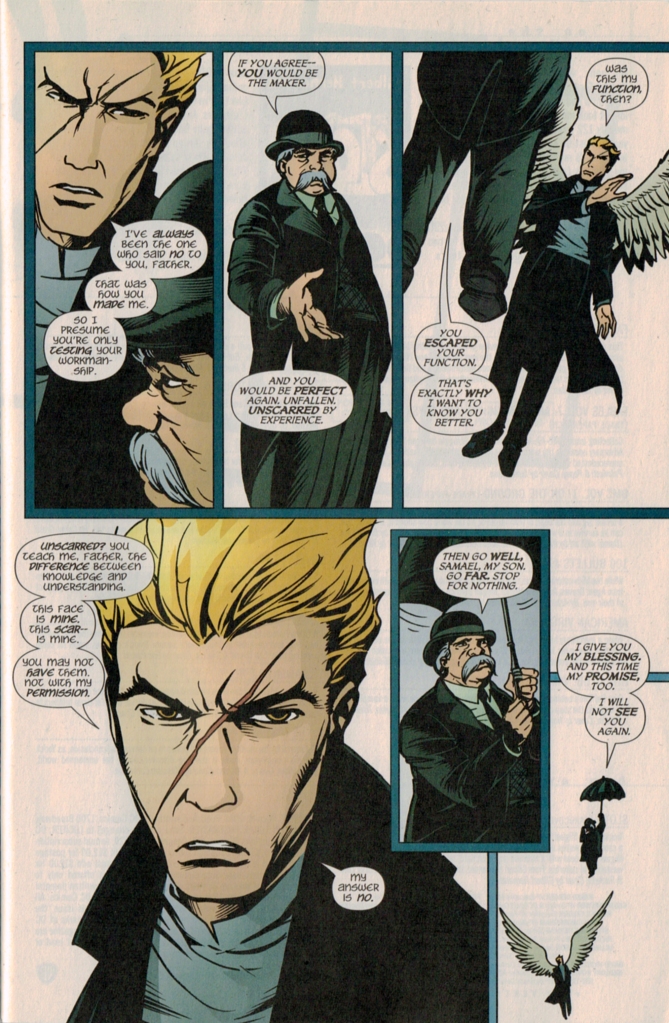

This conundrum forms the core of Mike Carey’s run on Lucifer. Lucifer left Hell easily. He clearly wasn’t needed to fulfill that role. But the question of whether he was simply a pawn in the grand design of his creator was what he continued to rebel against. Is fate determined, is there free will, or is there a third option?

In the series finale God offers Lucifer the chance to merge with him, creating a new entity that would lose the individual experiences of their previous existences. Lucifer (now sporting a facial scar that summons to mind Aladdin Sane’s lightning bolt), refuses to give away his personal identity in exchange for omniscience.

Figure 11. Carey, M. [w], Gross, P. [a], (2014). Lucifer: Book Five. Burbank. New York: DC Comics. © DC Comics.

Carey explains, ‛He (Lucifer) asserts his own autonomy against his father’s wishes and denies him the one thing he can effectively deny – himself. Obviously that self is still contingent, in the sense that all things in Yahweh’s cosmos are created and defined by Yahweh, but it belongs to Lucifer in a more profound sense.’ (M. Carey, personal communication, July 13, 2016). What this seems to imply is that what anyone owns, whether determined or freely chosen, is personal experience, and the responsibility that goes with it. Carey continued, ‛Even omniscience has a limit, and that limit is the qualia of another person’s experience. To know Lucifer fully you have to be Lucifer, and Yahweh isn’t.’ (M. Carey, personal communication, July 13, 2016). This is what it means to be self-aware. This is what enlightenment means. Each person is the sum total of their experience, and no one else, not even God, can understand what it means to have embodied that experience. As Ziggy said, ‛You better hang on to yourself.’ (Bowie, 2002).

‛Just a Mortal With Potential of a Superman’ (Bowie, 1990).

So why does the image of David Bowie resonate so clearly with the idea of Lucifer the Light Bringer? As we have seen, both Bowie and the devil have worn many faces (Gettings, 1988). In his definition of his concept of the Persona, Carl Jung says it is ‛a kind of mask, designed on the one hand to make a definite impression upon others, and on the other to conceal the true nature of the individual.’ (Jung, 2012). Bowie’s various personas have been masks, guarding his true self from public perception. He has repeatedly made provocative statements to the press that may or may not be true. In this way Bowie is a Lord of Lies. Glam rock, of which Bowie was a progenitor, takes its name from the word glamour, which in its archaic form meant magic and enchantment and can refer to an illusory quality. One of the indictments of Glam rock that has been leveled against Bowie is that it lacks authenticity (Auslander & Ausl, 2006). This implies that it is a lie and somehow less because of it. By contrast, in Beyond Good and Evil Nietzsche said, ‛Every profound spirit needs a mask.’ (Nietzsche & Kaufmann, 2010).

The name Ziggy Stardust alluded to the idea that we are all physically composed of material made in the hearts of stars. We are children of light and should strive to return to it. Ziggy arrived to blow our minds with the idea that we could be more than what we are. In the final days of his life, David Bowie released the album Blackstar. In the video for the song Lazarus, named after a man who was resurrected from the dead, we see Bowie, now old and aware of his impending death, dressed in the same outfit he wore on Station to Station. ‛Look up here, I’m in Heaven,’ the song begins. (Bowie, 2016). The Starman that was waiting in the sky fell to earth and became embodied in human consciousness. The lightning that descended from Kether to Malkuth to give him life has now ascended and returned home, his task and mighty labor accomplished.

To return to Mike Carey’s quote at the beginning of this article, he defined ‛Yahweh as the power that limits and defines, and Lucifer as the power that pushes against limits and transgresses.’

The latter sounds like as good a definition of David Bowie as any.

Endnotes

1In a personal email on July 16, 2016 Christopher Moeller (cover artist for the DC Vertigo Lucifer series) said ‟The Bowie connection never came up. I based my Lucifer on Yul Brenner (!), and also of course, on the established character.”

2The term had appeared in an article entitled ‟How Nuclear Radiation Can Change Our Race,” in the December, 1953 issue of Modern Mechanix, written by Otto Binder, author of many comic books, most notably the Golden Age Captain Marvel and illustrated by comics artist Kurt Schaffenberger.

3The letters of the word SHAZAM each stands for the power of a different god or hero. S for the wisdom of Solomon, H for the strength of Hercules, A for the stamina of Atlas, Z for the power of Zeus, A for the courage of Achilles, and M for the speed of Mercury.

4Originally published in Great Britain as Marvelman in 1982. Published in America as Miracleman by Eclipse Comics in 1985.

5We see this sequence reenacted for several other characters in the series.

References

Anorak. (2014, February 23). 1976: David Bowie’s “Nazi Salute” and Eric Clapton’s “Wogs” Created Rock Against Racism |. Retrieved August 21, 2016, from Flashbak, http://flashbak.com/1976-david-bowies-nazi-salute-and-eric-claptons-wogs-created-rock-against-racism-5645/

Ananke. (1999). Retrieved August 21, 2016, from https://gnosticteachings.org/glossary/a/1926-ananke.html

Auslander, P., & Ausl, P. (2006). Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Beaty, B., & Weiner, S. (2012). Critical Survey of Graphic Novels: Heroes & Superheroes (Vol. 1). Ipswich, MA: Salem Press. Lucifer by Gregory Steirer.

Berg, R. P. S., & Berg, P. S. (2004). The Essential Zohar: The Source of Kabbalistic Wisdom. United States: Crown Publishing Group.

Boboltz, S. (2016, January 11). The 1972 David Bowie Performance That Jumpstarted the 21st Century. Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/david-bowie-top-of-the-pops_us_5693ff52e4b0cad15e65ac86

Bowie, David. 2016. Blackstar. January 8, 2016. Columbia. [CD].

Bowie, David. 2016. ‛Hang on to Yourself’ (vocal performance). On The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars 30th Anniversary 2 CD Edition. [CD].

Bowie, David. 1990. Hunky Dory. EMI Records, Ltd. [CD].

Bowie, David. ‛It Ain’t Easy’ (vocal performance). On The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars 30th Anniversary 2 CD Edition. [CD].

Bowie, David. 2016. ‛Lazarus’ (vocal performance). On Blackstar. [CD].

Bowie, David. 2016. Lazarus. YouTube video, 4:08. Posted on Jan 7, 2016. Accessed August 29, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y-JqH1M4Ya8

Bowie, David. ‛Oh You Pretty Things’ (vocal performance). On Hunky Dory.

Bowie, David. 2003. Reality. September 16, 2003. Columbia. [CD].

Bowie, David. 1990. Space Oddity. Rycodisc. [CD].

Bowie, David.‟Starman” (vocal performance). On The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars 30th Anniversary 2 CD Edition. [CD].

Bowie, David. 1999. Station to Station.Virgin. [CD].

Bowie, David. 1997. The Man Who Sold The World. Rycodisc [CD]

Bowie, David. 2002. The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars 30th Anniversary 2 CD Edition. EMI Records, Ltd. [CD].

Brod, H. (2012). Superman is Jewish? How Comic Book Superheroes Came to Serve Truth, Justice, and the Jewish-American way. Alexandria, VA, United States: The Free Press.

Campbell, J. (2012). The Hero With a Thousand Faces (3rd ed.). United States: New World Library.

Campbell, J., & Moyers, B. D. (1988). The Power of Myth. New York, NY: Doubleday Books.

Carey, M., Gross, P., Kelly, R., Ormston, D., Hampton, S., Weston, C., Hodgkins, J. (2013). Lucifer: Book One. Burbank. New York: DC Comics.

Carey, M., Gross, P., Kelly, R., Doran, C., Kaluta, Michael Wm., Cannon, Z., Ormston, D., (2014). Lucifer: Book Five. Burbank. New York: DC Comics.

Crowe, C. (1976, February 12). David Bowie: Ground Control to Davy Jones. Retrieved August 21, 2016, from Music, http://www.rollingstone.com/music/features/ground-control-to-davy-jones-19760212

Crowe, C. (2006, May 18). All Access Bowie. Rolling Stone.

Cybulska, E. (2012). Nietzsche’s Übermensch: A Hero of Our Time? Retrieved August 21, 2016, from https://philosophynow.org/, https://philosophynow.org/issues/93/nietzsches_ubermensch_a_hero_of_our_time

Doggett, P. (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. London: Vintage.

Edwards, H., & Zanetta, T. (1986). Stardust: The David Bowie Story. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ellis, B. (2003). Lucifer Ascending: The Occult in Folklore and Popular Culture. United States: The University Press of Kentucky.

Gaiman, N., Kieth, S., Dringenberg, M., Jones, M., Klein, T., Busch, R., … Wilson, P. F. (2003). The Sandman, Volume 1: Preludes and Nocturnes (17th ed.). New York: DC Comics.

Gaiman, N., Jones, K., Dringenberg, M., Jones, M., Klein, T., Oliff, S., … Ellison, H. (2011). Sandman, Volume 4: Season of mists. New York: DC Comics.

Geenie, G. (2016, April 24). Finding Bowie’s Ghost in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman. Retrieved August 21, 2016, from https://geengeenie.com/2016/04/24/david-bowie-sandman-neil-gaiman/

Gettings, F. (1988). Dictionary of Demons: A Guide to Demons and Demonologists in Occult Lore. Trafalgar Square.

Gillen, K., McKelvie, J., Wilson, M., & Cowles, C. (2014). The Wicked and the Divine: The Faust Act: Volume 1. United States: Image Comics.

Goddard, S. (2015). Ziggyology: A Brief History of Ziggy Stardust. London, United Kingdom: Ebury Press.

Hebrew Concordance: Hê·lêl — 1 occurrence. (1966). Retrieved August 21, 2016, from http://biblehub.com/hebrew/heilel_1966.htm

Heinlein, R. A. (1987). Stranger in a Strange Land. United States: Penguin Group (USA).

Hepworth, D. (2016, January 15). How performing Starman on top of the pops sent Bowie into the stratosphere. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2016/jan/15/david-bowie-starman-top-of-the-pops

Jung, C. (2012, December 13). The Meaning of Individualism. Retrieved August 21, 2016, from http://www.awaken.com, http://www.awaken.com/2012/12/is-analytical-psychology-a-religion/

Jurgens, D., Ordway, J., Simonson, L., Bogdanove, J., & Grummett, T. (2013). Death of Superman (new edition). Carlsbad, CA, United States: DC Comics.

Kirby, J., & Lee, S. (2009). Marvel Masterworks: The X-Men, Volume 1. United States: Marvel Enterprises.

Kohler, K. (2003). Heaven and Hell in Comparative Religion With special Reference to Dante’s Divine Comedy (1923). New York, NY, United States: Kessinger Publishing Co.

Loder, K. (1983, May 12). David Bowie: Straight Time. Retrieved August 21, 2016, from Music, http://www.rollingstone.com/music/features/straight-time-19830512

Mccabe, J. (Ed.). (2004). Hanging Out With the Dream King: Conversations with Neil Gaiman and His Collaborators. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics.

Milton, J. (2007). Paradise Lost – A Poem Written in Ten Books: Text and Essays. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Moore, A., Davis, A., & Leach, G. (1988). Miracleman Bk. 1: A Dream of Flying. Peabody, MA, United States: Eclipse Books.

Morrison, G. (2011). Supergods: What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God From Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human. New York: Spiegel & Grau.

Nietzsche, F., & Kaufmann, W. (2010). Beyond Good and Evil: A Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Nietzsche, F., Kauffmann, W., & Hollingdale, R. J. (1974). Thus Spake Zarathustra; A Book For Everyone and No One. Baltimore: Penguin Group (USA).

Rauch, S. (2003). Neil Gaiman’s the Sandman and Joseph Campbell: In Search of the Modern Myth. United States: Wildside Press.

Sergi, J. (2012, September 19). The Amazing Adventure of the Man of Steel and the Psychiatric Censor — Superman vs. Doctor Wertham. Retrieved August 21, 2016, from http://cbldf.org, http://cbldf.org/2012/09/the-amazing-adventure-of-the-man-of-steel-and-the-psychiatric-censor-superman-vs-doctor-wertham/

Siegel, J., & Shuster, J. (2006). Superman Chronicles: Volume 1. New York, NY, United States: DC Comics.

LaVey, A. S. (1992). The Satanic Bible. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Thompson, D. (2009). Your Pretty Face is Going to Hell: The Dangerous Glitter of David Bowie, Iggy Pop, and Lou Reed. San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books.

Trynka, P. (2011). David Bowie – Starman. United Kingdom: Little Brown and Company.

V., & Fagles, R. (2006). The Aeneid. New York: Viking.

Watts, M. Oh You Pretty Thing – 22 January 1972 (1/2). Retrieved August 21, 2016, from http://www.5years.com, http://www.5years.com/oypt.htm

Werblowsky, R. Z. J., Jung, C. G., London, R., & Paul, K. (1973). Lucifer and Prometheus: A Study of Milton’s Satan,. United States: AMS Press.

Wertham, F. (1972). Seduction of the Innocent. Port Washington: New York, Rinehart [c1954].

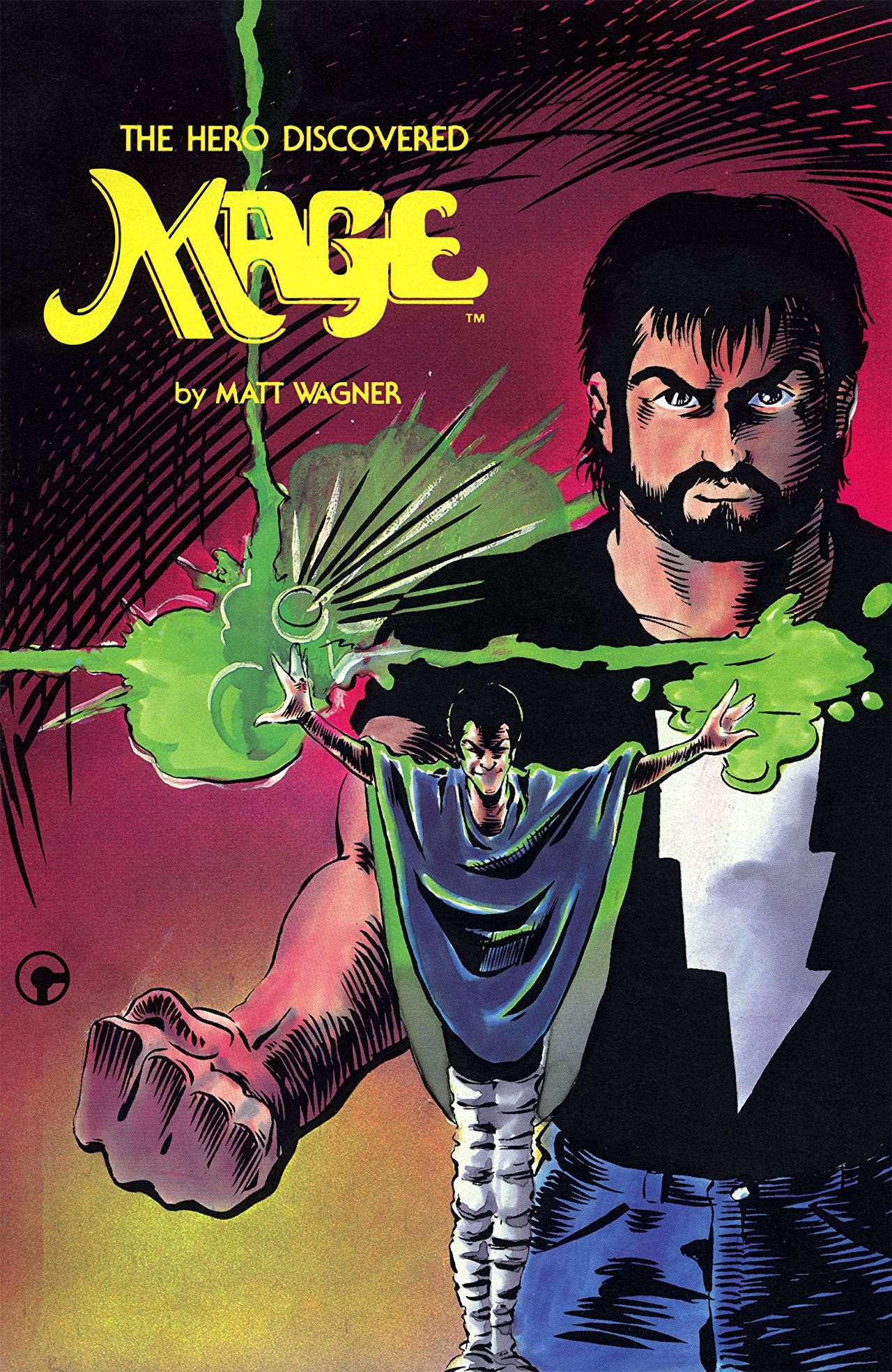

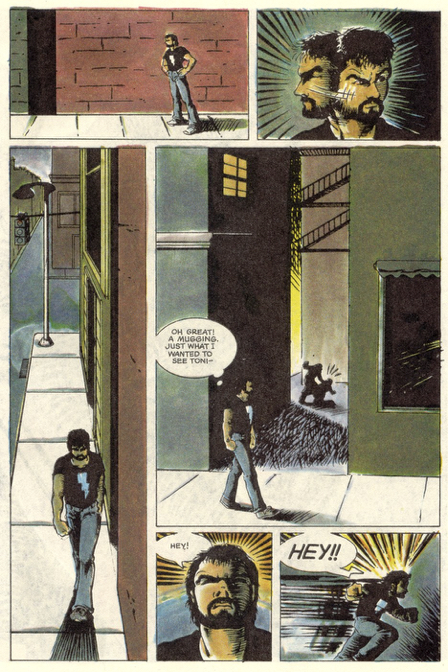

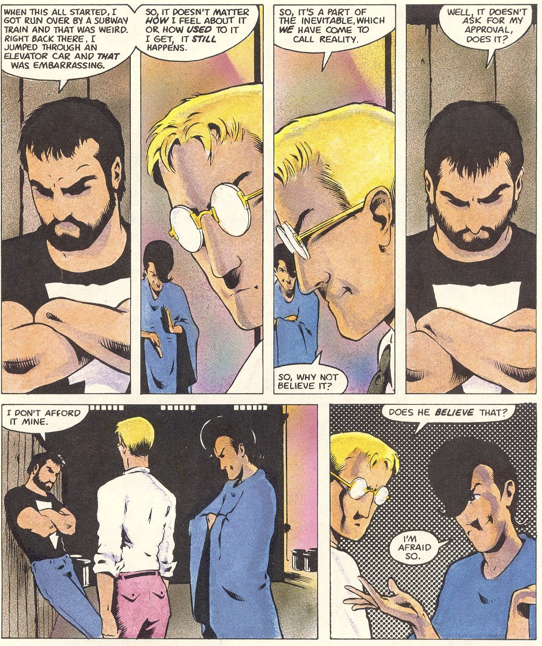

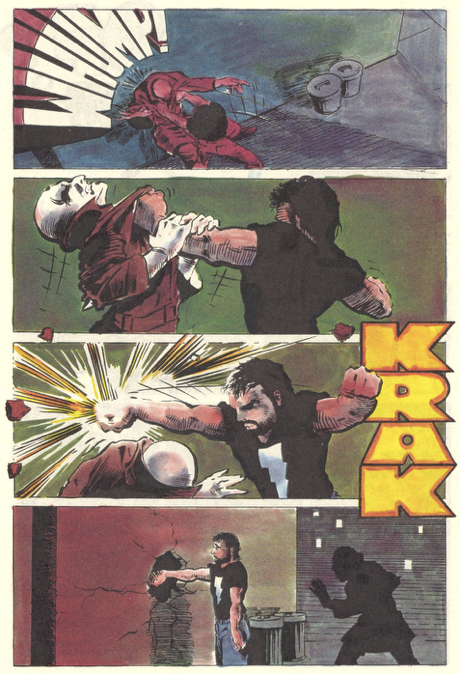

Shortly after meeting Mirth, Matchstick heeds the Call to Adventure. He sees a homeless man getting mugged in an alley and rushes in to save him. Kevin immediately recognizes that this act is significantly out of character for him. This is because the most salient aspect of the Heroes Journey that Matchstick embodies in the first series is that of the Refusal of the Call. Time and again, in spite of monsters and magic all around him, Matchstick refuses to accept his destiny. He is led by circumstances he thinks of as beyond his control. Mirth provides leadership and Kevin’s companions are more committed to the mission than he is.

Shortly after meeting Mirth, Matchstick heeds the Call to Adventure. He sees a homeless man getting mugged in an alley and rushes in to save him. Kevin immediately recognizes that this act is significantly out of character for him. This is because the most salient aspect of the Heroes Journey that Matchstick embodies in the first series is that of the Refusal of the Call. Time and again, in spite of monsters and magic all around him, Matchstick refuses to accept his destiny. He is led by circumstances he thinks of as beyond his control. Mirth provides leadership and Kevin’s companions are more committed to the mission than he is.

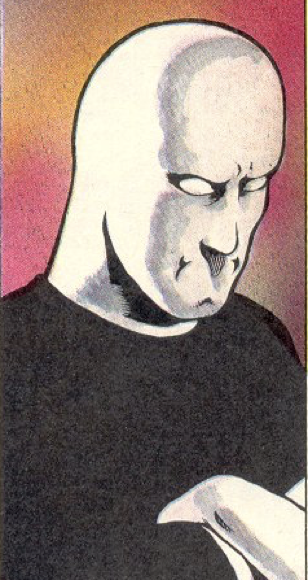

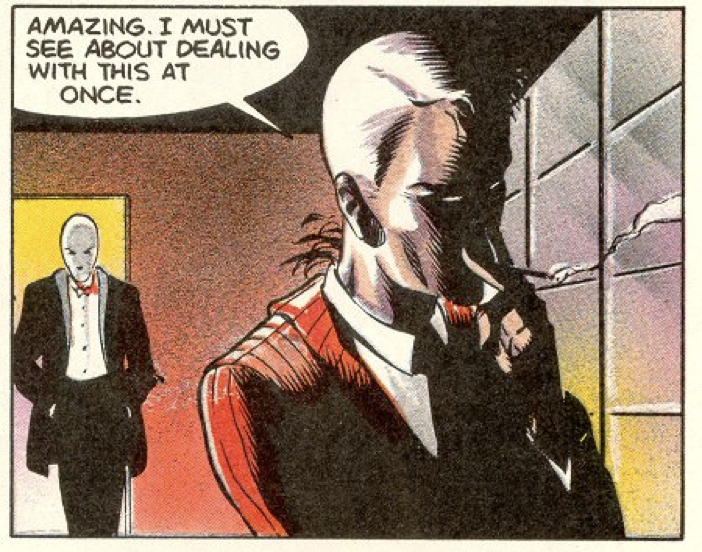

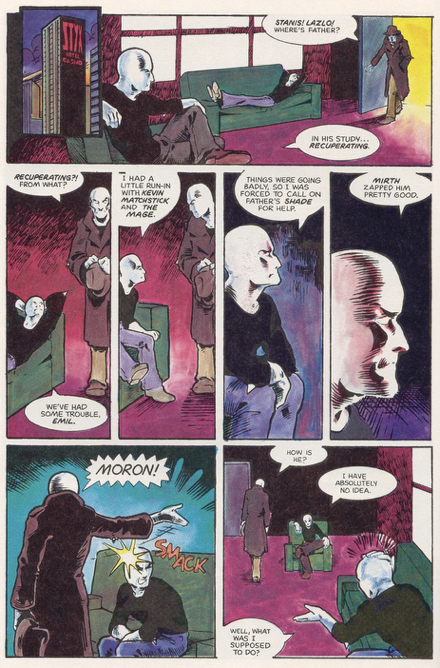

They are the sons of the Umbra Sprite, the main villain of the series. The Umbra Sprite wishes to usher in an age of darkness by finding and killing the legendary Fisher King. He is a distant villain who prefers to do his dirty work through the expendable hands of his children. Each of the brothers has a specific power; Stannis can fly, Piet is a shapechanger, Radu can turn invisible, and Laslo has the power to recognize the true identity of the Fisher King, who is a shapechanger in this incarnation. Emil, it seems, exhibits no special ability.

They are the sons of the Umbra Sprite, the main villain of the series. The Umbra Sprite wishes to usher in an age of darkness by finding and killing the legendary Fisher King. He is a distant villain who prefers to do his dirty work through the expendable hands of his children. Each of the brothers has a specific power; Stannis can fly, Piet is a shapechanger, Radu can turn invisible, and Laslo has the power to recognize the true identity of the Fisher King, who is a shapechanger in this incarnation. Emil, it seems, exhibits no special ability.

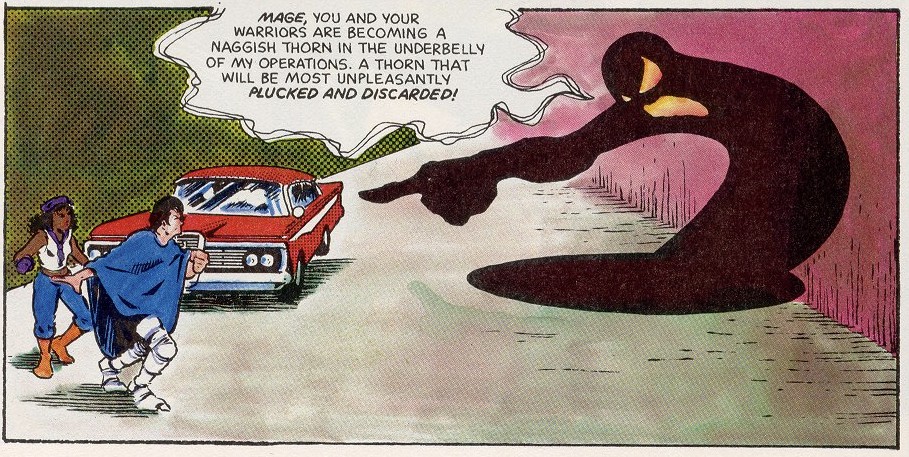

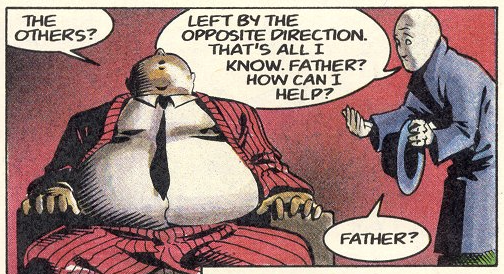

The Umbra-Sprite embodies the Shadow aspect of the Magician as well, and in this way mirrors Mirth. He sees Mirth as the true threat, mainly because Kevin has not yet come fully into his power. He is what Moore and Gillette refer to as the Detached Manipulator.

The Umbra-Sprite embodies the Shadow aspect of the Magician as well, and in this way mirrors Mirth. He sees Mirth as the true threat, mainly because Kevin has not yet come fully into his power. He is what Moore and Gillette refer to as the Detached Manipulator.

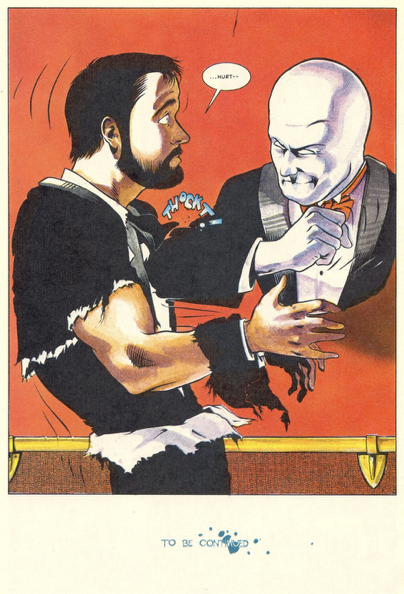

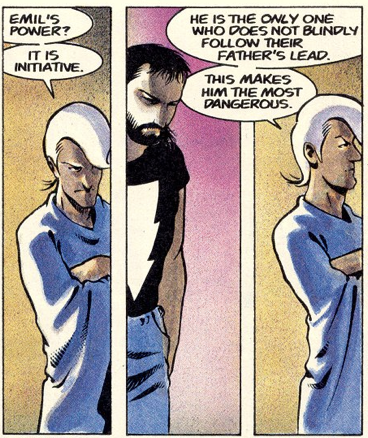

Emil is the Grackleflint who has the most individual personality. The others are only distinguishable by their powers, not by any specific personality traits. It is Emil who exhibits leadership among his brothers when their father is distracted by his own addiction to power. Time and again in the story we see Emil challenge his father’s authority, even at the risk of punishment. There is a reason he is able to do so.

Emil is the Grackleflint who has the most individual personality. The others are only distinguishable by their powers, not by any specific personality traits. It is Emil who exhibits leadership among his brothers when their father is distracted by his own addiction to power. Time and again in the story we see Emil challenge his father’s authority, even at the risk of punishment. There is a reason he is able to do so.

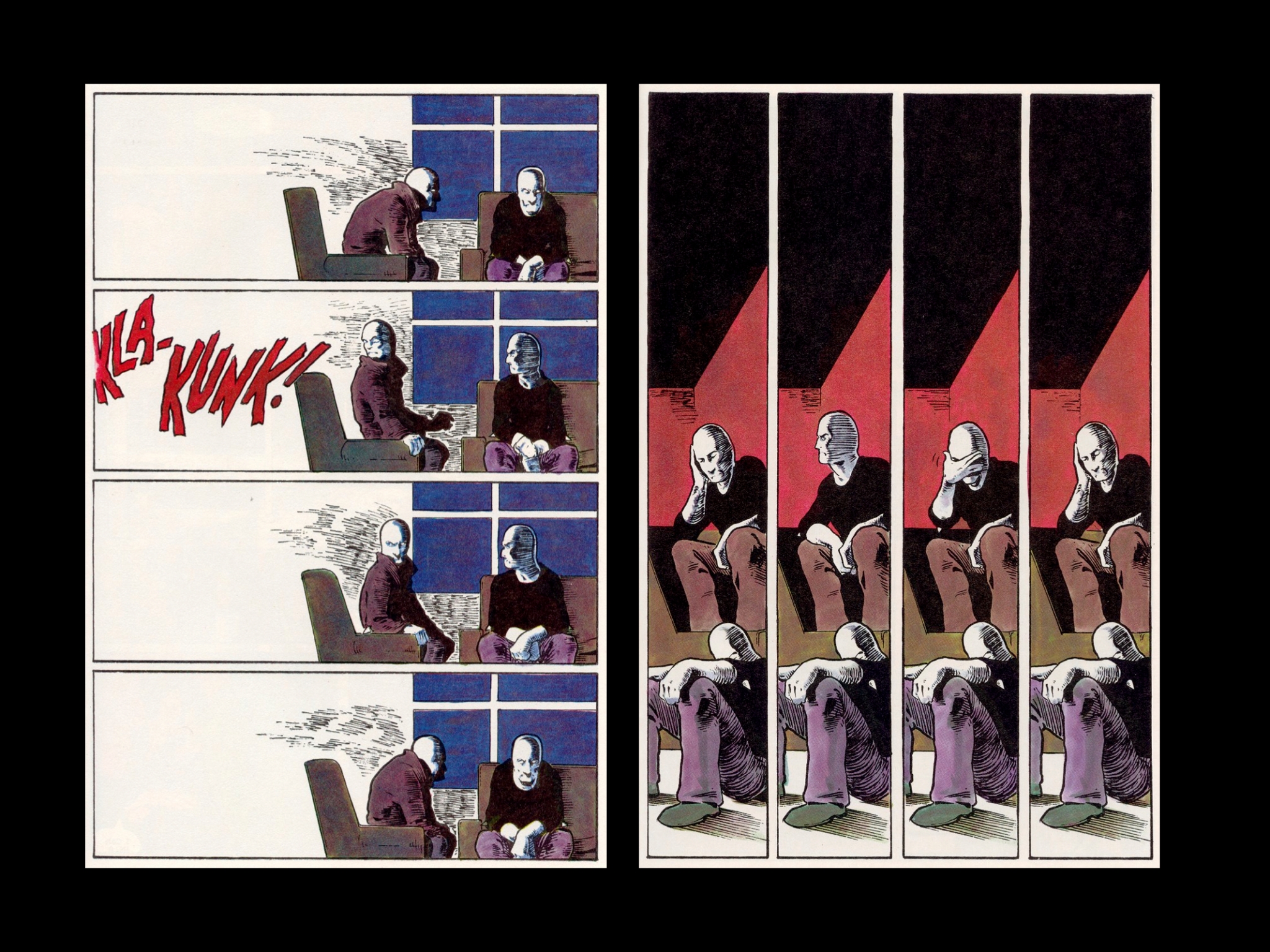

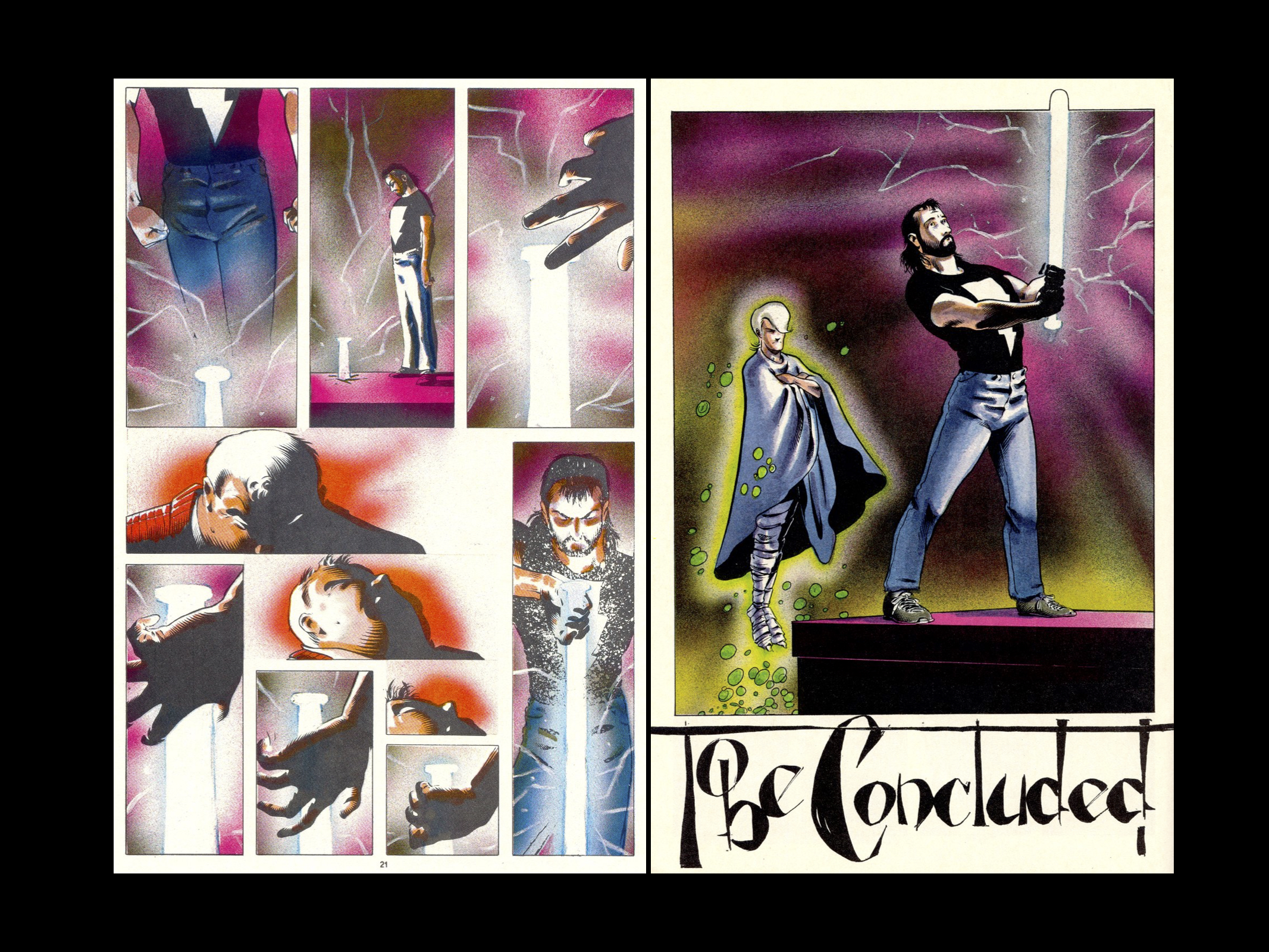

Emil also has an ending and a beginning. His father, bloated with his own excessive use of power and drained of all will, and initiative, sits and waits for Mirth and the Pendragon to arrive. Emil, left to his own devices, fulfills the quest the Umbra-Sprite has forsaken and finds the Fisher King in the guise of a three-legged cat. Unfortunately he has not been properly prepared by his father and does not know what to do. In the traditional Grail stories, specifically those of Chrétien de Troyes, it is the knight Perceval who finds the Fisher King, who is wounded. To condense the story significantly it is only through an act of compassion that Perceval is able to obtain the Grail and its power.

Emil also has an ending and a beginning. His father, bloated with his own excessive use of power and drained of all will, and initiative, sits and waits for Mirth and the Pendragon to arrive. Emil, left to his own devices, fulfills the quest the Umbra-Sprite has forsaken and finds the Fisher King in the guise of a three-legged cat. Unfortunately he has not been properly prepared by his father and does not know what to do. In the traditional Grail stories, specifically those of Chrétien de Troyes, it is the knight Perceval who finds the Fisher King, who is wounded. To condense the story significantly it is only through an act of compassion that Perceval is able to obtain the Grail and its power.

Emil has attempted to become a new dark lord and serves as the main ‟villain” of the story. He wears the costume of a dark lord, but throughout he seems to be play-acting the role. His initiative is gone, and like his father before him, he lurks in the shadows, using others to do battle for him. His master plan is to drain the energy of the Pendragon to fuel an engine of destruction. Neither he nor Kevin can see the larger picture and both become embroiled in their own, narrow agendas. At the end of this chapter, both of them fail.

Emil has attempted to become a new dark lord and serves as the main ‟villain” of the story. He wears the costume of a dark lord, but throughout he seems to be play-acting the role. His initiative is gone, and like his father before him, he lurks in the shadows, using others to do battle for him. His master plan is to drain the energy of the Pendragon to fuel an engine of destruction. Neither he nor Kevin can see the larger picture and both become embroiled in their own, narrow agendas. At the end of this chapter, both of them fail.